They marched for freedom

(These reflections originally appeared in the August 15, 2013 issue of the Catholic Standard marking the 50th anniversary of the March on Washington. Stories by Mark Zimmermann; photos by Michael Hoyt)

‘It was a sight I’ll never forget’

Fifty years ago this month, Reggie Tobias participated in one of the most famous marches in U.S. history – on his bike.

Fifty years ago this month, Reggie Tobias participated in one of the most famous marches in U.S. history – on his bike.

Tobias, who is now 67, is a native Washingtonian and serves as the assistant supervisor for security at the Basilica of the National Shrine of the Immaculate Conception, where he has worked for the past 13 years after a 33- year career with the D.C. Department of Public Works.

Early on the morning of the March on Washington on Aug. 28, 1963, Tobias and his three best friends bicycled down to the Lincoln Memorial. “We knew what was happening in the South… We went to see what was going on.

We were curious. When we got there, seeing all those thousands of people, it was amazing, all around the Reflecting Pool, all the way down. It was a sight I’ll never forget.”

For the 17 year old, venturing there around 8 a.m. not only got them a prime viewing spot.

“We went on the right side of the Lincoln Memorial. That’s where I met a lot of stars. I met Burt Lancaster, Lena Horne, Sidney Poitier and Harry Belafonte. I shook their hands. Burt Lancaster rubbed my head.”

The star-struck teen remembers seeing a lot of nuns in the crowd. From his vantage point, he saw the back of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.’s head. The youth was transfixed by the civil rights leader’s dream of a world, with “black kids and white kids in harmony and peace one day. That’s what shook me.”

He remembers that after Dr. King’s speech, the crowd “stood up and waved like this, side by side.” He smiled and remembered his immediate concern at the time: “I had trouble getting my bike out of there!”

Tobias no longer has that bike. At the time of the march, he and his family attended St. Luke Parish in Washington. Now he and his wife of 42 years, Mary, are members of Holy Redeemer Parish in the city. The National Shrine has become his second home. “This is a holy place. It’s like another world,” he said.

And he said he hopes the message of the March on Washington and Dr. King’s dream will be taken to heart by Americans today. “We need to live it, you know.”

‘It was my duty’

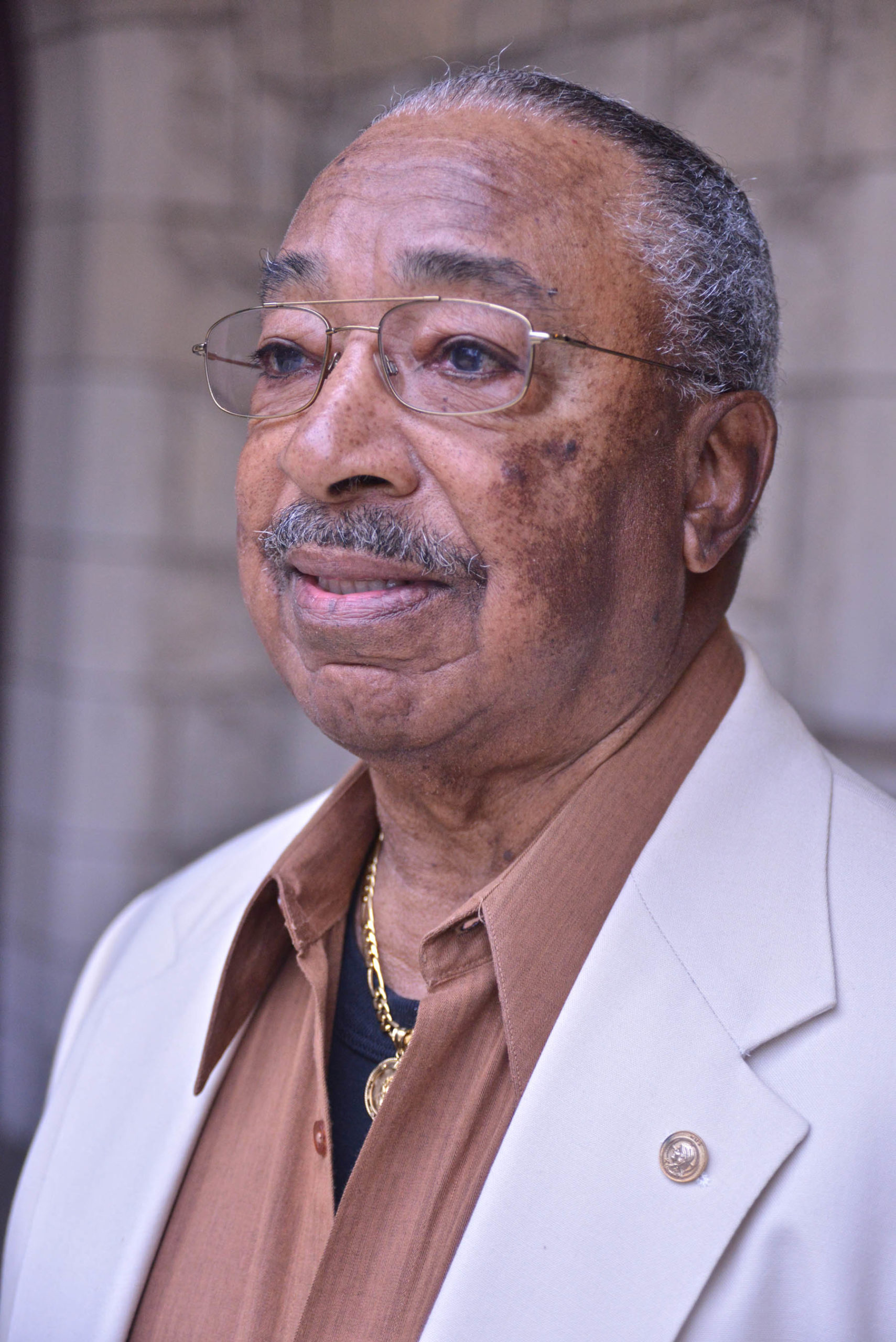

Walter Robinson has lived a life where he has been faithful to the call of duty – duty to his country, duty to his family and duty to God.

Walter Robinson has lived a life where he has been faithful to the call of duty – duty to his country, duty to his family and duty to God.

Now 92, he has worked as a security guard at the National Shrine for the past 22 years.

He and his late wife, Adell, have four children, four grandchildren and eight great-grandchildren. Over the years, he has worshipped in Baptist and Methodist churches, and now he feels blessed to serve at the shrine. “I’m working because I want to stay active,” he said.

On Aug. 28, 1963, he was 42 and working as a medical technician at Army Medical Center – the old Walter Reed Hospital. During World War II, he served as a combat medic with the Buffalo Soldiers Division, the nickname for the 92nd Infantry Division, an all-black unit of soldiers who fought as part of the 5th Army in Italy.

He joined the crowds of people marching together through the city of Washington as part of the March on Washington, and stood

among them as they heard Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. deliver his stirring “I Have a Dream” speech from the steps of the Lincoln Memorial.

“They kept coming in,” Robinson said of the crowd. “It was my duty to back him (Dr. King) up. It was for freedom, and to update the situation of minorities and underprivileged people.”

The march and Dr. King’s speech, he said, “touched me because of what I had witnessed, being in the Army. I was drafted. I went in there to fight for freedom.”

Now 50 years after that historic march, he said there is still a need “to bring people closer together,” so people of different backgrounds can recognize the humanity in each other, and stand together in the effort to provide more jobs and opportunities for the underprivileged in our United States of America.

‘We had to go!’

Marguerite Leonard had heard the warnings, people encouraging her not to go downtown for the March on Washington, because violence could erupt in that large crowd.

Marguerite Leonard had heard the warnings, people encouraging her not to go downtown for the March on Washington, because violence could erupt in that large crowd.

“My goodness, we had to go!” said Leonard, who is now 83 and a member of St. Catherine Labouré Parish in Wheaton. “We just believed in what he (Dr. King) was saying, (we believed in) the cause.”

And so at noontime, she and her sister Jackie, also a government worker, left Capitol Hill and took the afternoon off to join the

march. Leonard was then 33, not yet married, a young woman of Irish-American descent and a member of St. James Parish in

Mount Rainier working as a secretary for a House subcommittee. Her future husband, Edward Leonard, was in the crowd too, but she didn’t know it at the time.

What she saw that afternoon continues to inspire her, 50 years later. People came in from all over the country, stepping from buses and marching together. “They had a cause, and they were dedicated to it.” The dire predictions proved wrong. “It was so peaceful, orderly and respectful,” Leonard said. “I’m glad we went.”

Mrs. Leonard and her husband, who is now deceased, have three children, including Catholic Standard contributing writer Maureen Leonard Boyle, and three grandchildren.

On this 50th anniversary of the march, Mrs. Leonard remembers the thrill of hearing Dr. King’s speech. Those words, and the need for people of different backgrounds to stand together for the right thing, remain as absolutely vital today as they did then, she said.

“It was such an American thing to do. It felt so right to be there.”

‘Those words hit home’

That day 50 years ago, Mary Shearard was the lucky one of the 13 children of Ruby and Cyprian Tilghman. On the morning of the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom, Cyprian Tilghman, who headed the Hotel and Restaurant Workers Union in Washington, picked his 17-year-old daughter Mary to accompany him.

That day 50 years ago, Mary Shearard was the lucky one of the 13 children of Ruby and Cyprian Tilghman. On the morning of the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom, Cyprian Tilghman, who headed the Hotel and Restaurant Workers Union in Washington, picked his 17-year-old daughter Mary to accompany him.

“Out of the 13 children, I’m the one (to whom) he said, ‘Let’s go!’” remembered Shearard. Today she is a member of Our Lady of Perpetual Help Parish in Washington, where her youngest brother, Deacon Timothy Tilghman, serves.

The recent graduate of Spingarn High School went with her dad to his union’s offices at 14th Street, where they joined other marchers. “Since the march was for jobs and freedom, the unions were heavily involved…There was a need for jobs for so many people.” The head of the March on Washington, A. Philip Randolph, led the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters, the nation’s first predominantly black labor union, and his bronze bust is now displayed at Union Station.

But Mary Shearard didn’t go just to tag along with her father. She said her older siblings had experienced discrimination from classmates and even teachers at their newly integrated schools, and she felt “it was important for me, as a young black female who lived in Washington, D.C.,” to march. At her home, she had watched TV and seen the images of civil rights marchers in the South being confronted with firehoses and dogs.

“That was a time when I felt like, maybe we can rise above this.”

The day, and the sight of the massive crowd, were beautiful, she said. “It was awesome to be in the midst (of that)… We were in a place just beyond the Reflecting Pool.

We had a view of the steps of the Lincoln Memorial.” From her vantage point, she could see Dr. King and the other civil rights leaders, including Dr. King, John Lewis and Ralph Abernathy.

As Dr. King spoke, the crowd was hushed. “It was reverent, almost like a church atmosphere,” she said, remembering how the crowd erupted in joy afterward.

When he spoke about children being judged not by the color of their skin, but by the content of their character, “those words hit home to me,” Shearard said.

Shearard grew up in a devout Catholic home, with her family attending the old St. Cyprian Parish, then Incarnation and St. Luke parishes in the city. Many of the civil rights leaders and marchers came from various faith traditions, and she said that spirit is needed today, as it was then. “For people of faith, it’s their duty, their responsibility, to stand up for what is right,” she said.

There is “still more work to do” in accomplishing Dr. King’s dream, she said, noting the challenges that President Obama has faced in the White House.

Now Shearard does administrative work for Symbiont, an information technology firm in Silver Spring. She is married to George Shearard, and she has three children, eight stepchildren and 21 grandchildren. She hopes the crowd for the 50th anniversary march on Aug. 28 will be even bigger than the first one. “It is my intent to be there again, with my children this time,” she said, expressing a desire to relive the experience and to join the effort to recommit our country to expanding jobs and freedom for all its people.

‘We’re living history!’

For JoAnn Adams, making the eight-hour bus ride from Boston to the nation’s capital for the March on Washington in August 1963 was a homecoming.

For JoAnn Adams, making the eight-hour bus ride from Boston to the nation’s capital for the March on Washington in August 1963 was a homecoming.

A D.C. native, she grew up attending Our Lady of Perpetual Help Parish and graduating from its school and St. Cecilia’s Academy.

She was the only black student in her graduating class in nursing school and was serving as a nurse at St. Elizabeth Hospital in Brighton, Mass., when she boarded the bus to come home.

“There was singing. It was like one big family. You just felt there’s a magic to it all, having the same mindset and cause and purpose.

You were meeting people you’d never seen before, but felt you knew them all your life,” she said of the mix of people on the bus, who were of different ages, races and backgrounds.

Once in the midst of the huge throng, she marveled at how beautiful her home city looked on this day, and focused her eyes on the Lincoln Memorial. “I remember sitting on the edge of the Reflecting Pool, dipping my feet in water to keep cool.”

Then Dr. King gave his unforgettable speech. “When Dr. King said, ‘I have a dream,’ my friend said, ‘JoAnn, we’re living history!’”

After the rally, her Boston contingent had to immediately board the bus and drive straight back. “There was a lot more singing. We were all very tired,” she remembered.

Adams later moved to St. Louis, where she continues to live, married, and had a daughter.

She stayed in nursing for a while, but then spent 13 years involved in another kind of bus – a Black History Bus Tour in that city.

The spirit of solidarity and joy in that crowd at the March on Washington still moves her, 50 years later – “just the sense of being in a crowd that large, and the sense that we were all friends, (and) everyone having a feeling of hope.”

‘I witnessed the whole thing’

Sitting in a pew after a recent Sunday Mass at St. Augustine Church in Washington, Marion Cunningham, who is now 82, smiled and reflected on a day he will never forget – Aug. 28, 1963, the day he joined the March on Washington, starting out from that very church.

Sitting in a pew after a recent Sunday Mass at St. Augustine Church in Washington, Marion Cunningham, who is now 82, smiled and reflected on a day he will never forget – Aug. 28, 1963, the day he joined the March on Washington, starting out from that very church.

“I was there. I was there, yes indeed. I was there and witnessed the whole thing,” he said.

He took the day off from his job as a bookkeeper for a Washington real estate firm, and joined the parishioners who set out together for the march.

“Everybody was just so happy and enthusiastic and ready to march,” Cunningham said, remembering the trek of a few miles through the city. “Despite the fact it was a long walk, it didn’t seem long at all. We walked all the way to the Mall. We were singing, ‘We Shall Overcome.’”

The parish group dispersed once they reached the Mall, and he stood near the end of the Reflecting Pool, near where the World War II Memorial is now. “It was beautiful, a beautiful, sunny day, and everybody was so cordial to one another. I’ve never seen everybody so full of love. The crowd was phenomenal. People who didn’t know each other hugged… (there were) so many kids on parents’ shoulders, trying to get a peek.”

He appreciated the fact that Washington’s Archbishop Patrick O’Boyle gave the opening prayer – the archbishop had confirmed Cunningham at St. Matthew’s Cathedral after he had converted to the faith as a 20-year-old.

Cunningham described the racism that existed at that time, even in Catholic churches.

Some restaurants in the city made it clear that blacks were not welcome. “They would just ask you to leave, (and say) ‘We don’t serve blacks here.’” And he recalled a time when he tried to go to Confession at a Catholic church in the nation’s capital, and the pastor “asked if I was white or colored. I asked what difference it made. I had just become Catholic, and I was ready to leave (the Church).”

So the march was especially meaningful to Cunningham, he said. “We had the same purpose in mind, to try to rid this city and the whole United States of segregation.”

Dr. King, he said, seemed called to give that speech that day, “and he put his heart and soul into it.” Cunningham hurried home to watch the march unfold again, in television reports.

The march’s call for freedom and equality – expressed in Dr. King’s immortal “I Have a Dream Speech” – resonates today, 50 years later, Cunningham said. That message “is just as important today as it was the day he did it.”